In What Way is the Senate a Continuous Body What Does a Legislator

No. 9 - Origins of the Senate

The Senate is one of the houses of federal Parliament, the other being the House of Representatives. Democratically elected, and with significant legislative power, it is generally considered to be, apart from the Senate of the United States of America, the most powerful legislative upper chamber in the world.

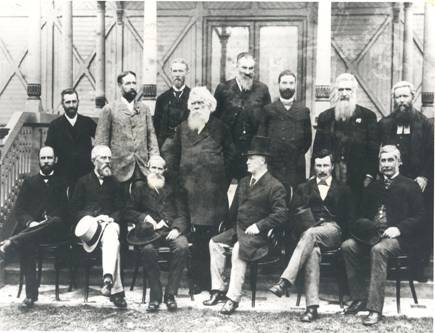

Delegates to the Australasian Federation Conference, Melbourne, 1890 Image: National Library of Australia

Federation

Federation of the Australian colonies had been proposed as early as 1848, but it was not until the 1890s that serious moves were made to bring it about. By then, Australia consisted of six British colonies, each self-governing in relation to domestic matters, each staunchly independent of the others, but all linked by a common culture and heritage and possessing a number of common interests.

Delegates from these colonies gathered at a convention in 1891 in Sydney at which they devised a constitution for a federated Australia. It made provision for a Senate intended to represent the states equally in the federal Parliament. However, the federal movement lost momentum in the years immediately following the convention and the colonial parliaments, preoccupied with the political and economic problems of the day, allowed the issue to lapse.

Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900:

original public record copy courtesy of Parliament House Art Collection, Canberra, ACT

The federal movement was revived during the second half of the decade. Another convention, known as the Australasian Federal Convention, was held during 1897 and 1898 in three sessions in Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne. As in 1891, a constitution for a federated Australia was framed. While not formally adopting the constitution drafted at the 1891 convention as their starting point, the delegates who attended this convention assumed it as the foundation of their work. However, significant changes were made to this constitution, many of which related to the Senate. Some minor amendments were made at a Premiers' Conference in Melbourne in 1899.

The constitution drafted at the 1897–8 convention was approved by the people of each colony at referendums held in 1899 (1900 in Western Australia). Further small amendments, primarily relating to appeals from the High Court to the Privy Council, were made by the British government in consultation with Australian negotiators in 1900, before the passage through the Parliament of the United Kingdom of the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900. An Act of that Parliament was necessary because at the time it was the highest law-making institution for the Australian colonies. The Constitution came into force on 1 January 1901.

Name of Senate

The names, 'The Senate' and 'The House of Representatives', were taken from the names of the houses of the United States Congress. Other names were put forward at various times at the constitutional conventions—for example, 'States Assembly' to replace the 'Senate'—but these gained little support.

Composition

The delegates to the conventions were intent on protecting their respective colonies' interests during the drafting of the Australian Constitution. In particular, the delegates from the less populous and wealthy colonies (Tasmania, Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia, usually referred to as the smaller colonies) were especially concerned to ensure that the proposed federal Parliament was not dominated, to their detriment, by the two most populous and wealthy colonies (New South Wales and Victoria, usually referred to as the larger colonies). The delegates looked to other great federations for guidance on such matters. In this case, they were influenced by the Constitution of the United States, which established a Senate which was composed of an equal number of representatives from each state. The other house of Congress, the House of Representatives, was composed of representatives from each state in proportion to population. The delegates to the 1891 convention adopted this structure for the proposed Australian federal Parliament and this decision was reaffirmed by delegates at the 1897–8 convention (see sections 7 and 24 of the Constitution). Most delegates considered that structuring Parliament in this way would mean that, in the words of Sir Samuel Griffith at the 1891 convention:

every law submitted to the federal parliament shall receive the assent of the majority of the people, and also the assent of the majority of the states.

Convention Debates, Sydney, 4 March 1891

As the smaller states would outnumber the larger states, their interests would be protected.

Election

The delegates to the 1891 Convention, again influenced by the Constitution of the United States, where, at that time, senators were appointed by state legislatures, agreed that senators would be appointed by state parliaments. It was agreed that they would be appointed for six year terms, twice the length of the terms for members of the House of Representatives. The Senate would have a continuous, but rotating membership, with half of the membership of the Senate being appointed every three years (see section 13 of the Constitution). This was intended to ensure that the Senate was independent of the executive government (which we usually refer to as 'the government' and which consists of the Prime Minister and the other ministers of state) on whose advice the Governor-General would usually act when dissolving a house of Parliament.

Two changes were made at the 1897–8 convention. The delegates to that convention agreed that senators ought to be directly elected by the people (see section 7 of the Constitution). In addition, a provision was included allowing for the dissolution of the Senate where the two houses of Parliament were 'deadlocked'.

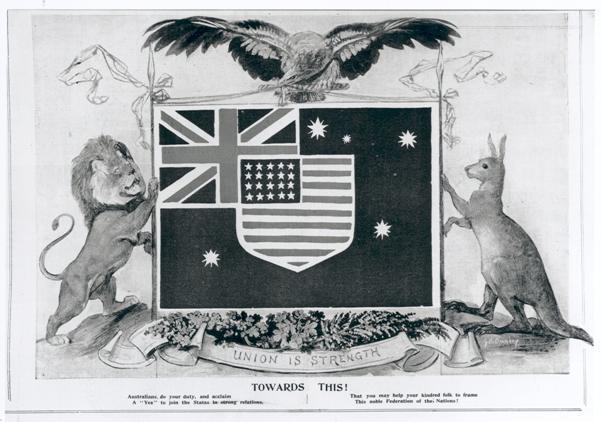

Elements of the parliamentary systems of a number of other countries were considered in the writing of the Australian Constitution.Image: National Library of Australia

Deadlocks

The Senate was to have nearly the same power over bills (that is, proposed legislation) as was to be possessed by the House of Representatives. The question eventually arose as to whether some mechanism should be inserted to resolve situations, known as deadlocks, where there was an unresolvable disagreement between the two houses over a bill. It was feared that deadlocks would be inevitable in a Parliament where one house was dominated by representatives from the larger states and one house by representatives of the smaller states. After lengthy discussion and argument, primarily during the Sydney and Melbourne sessions of the 1897–8 convention, the delegates decided that where a bill was initiated and twice passed by the House of Representatives, and twice rejected by the Senate, the Governor-General could dissolve both houses of Parliament. After the ensuing election, if the bill was passed again by the House of Representatives and rejected by the Senate, it would be deemed to have passed if an absolute majority of senators and members of the House of Representatives voted in its favour at a joint sitting of the two houses (see section 57 of the Constitution).

Many delegates from the smaller colonies opposed the erosion of the Senate's independence from the government that making it dissolvable would entail. In Sydney in 1897, James Howe of South Australia went so far as to describe this provision as being 'a Frankenstein' that would 'destroy our state rights'. However, delegates from the larger colonies insisted that their colonies would not enter the federation unless a deadlock provision was inserted, and the smaller colonies eventually gave way (see Senate Brief No.7).

Finance and responsible government

The true 'lion in the path of Federation' was the extent of the Senate's powers in relation to bills imposing taxation and appropriating money (money bills) and, in particular, whether the Senate should be able to amend them. It was generally accepted throughout the conventions of 1891 and 1897–8 that the Senate should be able to initiate and amend any type of bill except a money bill, and that it should be able to reject any bill.

Intertwined with this issue were broader concerns about the compatibility of 'responsible government' with federation. 'Responsible government' meant the system of government which had evolved in Great Britain, where the government was responsible solely to the popularly-elected House of Commons. Governments were formed and removed in accordance with the party numbers in that house. The other chamber, the unelected House of Lords, played no part in that process. In particular, it could not originate or amend money bills. (This was a matter of convention until it was made a matter of law in 1911.)

Money bills lie at the heart of government. Taxation bills raise revenue and appropriation bills authorise the government to spend that revenue. If the necessary revenue is not raised by the Parliament, or if the authorisation to spend revenue on proposed activities is not given by the Parliament, the proposed activities cannot be undertaken by the government. Ultimately then, the power to originate and amend money bills is the power to control the activities of the government.

The problem for the delegates at the 1891 and 1897–8 conventions was as follows. In Australia, the adoption of full British responsible government would have meant making the government responsible solely to the House of Representatives. Delegates from the larger colonies argued that this could only occur if that house, like the House of Commons, possessed the exclusive power to originate and amend money bills and, consequently, the exclusive power to control the activities of government.

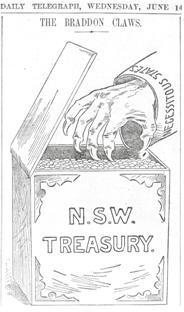

Image: National Library of Australia

In support of their demands for British responsible government, the delegates emphasised that most of the members of the House of Representatives would come from the larger states whose taxpayers would provide most of the revenue for the activities of the government. Richard O'Connor of New South Wales put it bluntly:

No body of people outnumbering the population of the smaller States as they do would put up with their dictation on such a matter as the expenditure of their money.

Convention Debates, Adelaide, 13 April 1897

These delegates argued that the Senate should only have the right, 'to be exercised in some great emergency', to reject money bills outright.

On the other side, Sir John Forrest of Western Australia, protested that, if the power to amend money bills was not granted to the Senate:

we may as well hand ourselves over, body and soul, to those colonies with larger populations.

Convention Debates, Adelaide, 13 April 1897

He and other delegates from the smaller colonies feared that the proposed federal government could act to the detriment of their states unless the Senate, most of whose members would come from the smaller states, possessed this power.

To grant the Senate the power to amend money bills would, however, have given it constitutional powers in relation to the government nearly the equal to those possessed by the House of Representatives. As many delegates from both large and small colonies recognised, this would make the government responsible to both houses of Parliament. Deadlocks on money bills would inevitably arise, during which the government would be paralysed.

Sir John Downer, Edmund Barton and Richard O'Connor, drafting committee of the Australian Constitution appointed during the Federal Convention, Adelaide, 1897. Image: National Library of Australia

The delegates to the 1891 convention responded to this dilemma in two ways. First, they did not mandate responsible government. Government ministers could be, but were not required to be, members of Parliament. The way was left open for the development of a system closer to that existing in the United States of America, where the President (who heads the government) and his Ministers (appointed by the President with the approval of the Senate) are not members of Congress, and the President governs for a fixed term of four years irrespective of whether the party he or she belongs to possesses a majority of seats in either or both Houses of Congress. Secondly, the Senate was prohibited from amending bills appropriating money for the ordinary annual services of government and bills imposing taxation but could amend other types of appropriation bills. However, it would be able to request amendments to bills it could not amend (see section 53 of the Constitution). This arrangement became known as the 'compromise of 1891'.

By 1897, however, there was a general consensus among delegates that ministers ought to be members of parliament (see section 64 of the Constitution). This left the issue of whether the Senate should have the power to amend money bills. The smaller colonies were adamant that it should. The larger states were equally adamant that it should not. The impasse was resolved only when six delegates out of a total of fifty, realising that federation itself was at stake, changed their votes and restored the 'compromise of 1891'. In their seminal work, The Annotated Constitution of the Australian Commonwealth (1901), John Quick and Robert Garran described this debate as the 'most momentous in the Convention's whole history' (p. 172).

After federation

The Senate first met on 9 May 1901 in the chamber of the Legislative Council of Victoria in Spring Street, Melbourne. It continued to meet there until the opening of the provisional Parliament House in Canberra on 9 May 1927. The Senate first sat in the new Parliament House in Canberra on 22 August 1988.

The design of the Senate was, like many aspects of the Constitution, a compromise that the delegates to the conventions believed would adequately protect the interests of all the states. It was also an institution into which life had 'yet to be breathed, and which the great force of national will' would thereafter 'shape into its own form and expression' (Alfred Deakin quoting Sir John Downer, Convention Debates, Adelaide, 13 April 1897).

Two developments after federation were of considerable significance for the Senate. First, as predicted by a number of delegates to the conventions, senators began to vote as members of political parties rather than as representatives of states. This somewhat obscured the value of state-based representation, although that system still ensures that legislative majorities cannot be made up of representatives of only the populous states.

Secondly, the retention of the 'compromise of 1891' had left the Senate possessing considerable legislative powers, even in relation to finance. While most delegates at the 1897–8 convention believed that a Senate with these powers was compatible with British responsible government, others were less sure. Sir Robert Garran wrote in 1897 that:

the parliamentary system for federal purposes may develop special characteristics of its own ... [T]he familiar rule that a Ministry must retain the confidence of the representative chamber may, in a Federation ... develop into a rule where the confidence of both chambers is required.

The Coming Commonwealth, 1897, p. 150.

This is what ultimately occurred. The government is now held responsible to both houses of federal Parliament, though in different ways. Government is formed by the party or coalition of parties possessing a majority in the House of Representatives. However, the Senate may force the government to account for its actions, and in the last resort to go to an election, by rejecting an appropriation bill for the ordinary annual services of government. The Senate closely scrutinises and judges the policies and activities of the government.

A major change to the Senate occurred in 1948 when the federal Parliament adopted the proportional representation electoral system for Senate elections, which is still used for Senate elections today (see Senate Brief No. 1). This system helps ensure that parties gain representation in proportion to their share of the vote. Its adoption has led to the smaller parties and independents gaining representation in the Senate and to the party or coalition of parties forming government rarely winning a majority of its seats. Consequently, the Senate's ability to review the activities and policies of government was strengthened considerably (see Senate Brief No. 10).

One other notable development occurred in 1970 when the Senate established a system of standing committees. Since that time the committee structure has further improved the Senate's ability to review the activities of government (see Senate Briefs No. 4 and 5).

Further reading

The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Australia.

Rosemary Laing (ed.), Odgers' Australian Senate Practice, 14th edn, Department of the Senate, Canberra, 2016

J.A. La Nauze, The Making of the Australian Constitution, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1972.

J. Quick & R.R. Garran, The Annotated Constitution of the Australian Commonwealth, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1901.

Convention Debates, Legal Books Pty Ltd, Sydney, 1986, Vol. I–VI.

B. Galligan & J. Warden, 'The Design of the Senate', in Convention Debates, Legal Books Pty Ltd, Sydney, 1986, Vol. VI, p. 89.

B. Galligan, 'The Founders' Design and Intentions Regarding Responsible Government', in Responsible Government in Australia, P. Weller & D. Jaensch (eds), Drummond Publishing (on behalf of the Australian Political Studies Association), Melbourne, 1980.

G. Sawer, 'Federalism', in The Australian Encyclopaedia, Australian Geographic Pty Ltd, Sydney, 1988, Vol. 4, p. 1222.

B. de Garis, 'Federation', in The Australian Encyclopaedia, Australian Geographic Pty Ltd, Sydney, 1988, Vol. 4, pp. 1223–9.

B. de Garis, 'How popular was the popular federation movement?' Papers on Parliament No. 21, December

Updated July 2017

Source: https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Senate/Powers_practice_n_procedures/Senate_Briefs/Brief09

0 Response to "In What Way is the Senate a Continuous Body What Does a Legislator"

Post a Comment